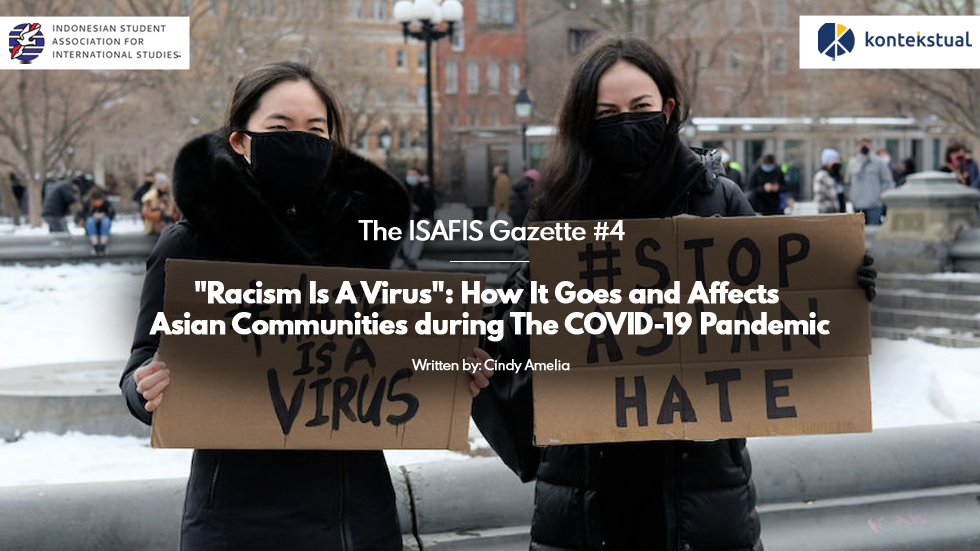

“Racism Is A Virus”: How It Goes and Affects Asian Communities during The COVID-19 Pandemic

Illustration from ISAFIS.

This article is originally published on ISAFIS’ Medium. Click here to be redirected.

In the last week of 2019, the world began to notice a peculiar report from Wuhan’s hospitals: an increase in pneumonia cases with unexplained origins. Soon, scientists found out that these cases were due to a new type of coronavirus, now popularly known as COVID-19 (Gover, Harper, & Langton, 2020). Sadly, as the virus originating from China spread around the world, so has prejudice, xenophobia, and racism. While it is common that anxiety and fear about the pandemic ended up widespread, racist incidents, including hate crimes and Asian-focused racism, have also occurred, particularly in the United States (Croucher, Nguyen, & Rahmani, 2020). The Asian population, which is also the fastest growing ethnic group in the US, has become targets of discrimination, harassment, racial slurs, physical attacks, and many forms of racism throughout this grim period in our history.

The FBI has issued a warranted warning that there may be an increase in hate crimes against Asian Americans due to COVID-19. This is because “a portion of the US public will associate COVID-19 with China and Asian American populations” (Tessler, Choi, & Kao, 2020). Based on a report from Stop AAPI Hate, in the one-month period from March 19th to April 23rd, there were nearly 1500 alleged instances of anti-Asian bias. The reported incidents have been concentrated in New York and California, with 42% of the reports hailing from California and 17% of reports from New York.

However, Tessler, Choi, & Kao stated that it is important to highlight how discrimination against Asian Americans is actually a nation-wide issue in the US. According to BBC News, a reporting centre run by advocacy groups and San Francisco State University said they received over 1,700 reports of coronavirus-related discrimination from at least 45 US states since it launched in March (Cheung, Feng, & Deng, 2020). The incidents included verbal harassment, shunning, physical assault, workplace discrimination, barred from establishments, and vandalism. Simply speaking, it seemed as if the entire US population is blaming the entire Asian population for the pandemic. With their hold on media coverage and framing, this issue might just promote racism towards Asian globally.

In June 2020, the Pew Research Center surveyed 9,654 US adults and found that, since the start of the corona-virus outbreak, 31% of Asians have been subjected to slurs or jokes because of their race/ethnicity. This is quite a number if compared to other minority counterparts in the country, such as 21% for Blacks, 15% for Hispanics, and 8% for whites. In addition, 26% of Asian Americans said that they feared someone might threaten or physically attack them. Moreover, according to Wu, Qian, and Wilkes (2020), a nation-wide survey found that more than 40% of US adults agreed that “it has become more common for people to express racist views toward Asians”. It was pointed out that Asians’ ongoing experiences of microaggressions and racial discrimination during the pandemic contribute to not only the presence of race-related stress, but also race-based trauma. Additionally, experiences of racial discrimination can threaten individuals’ identity and sense of control, thereby leading to hopelessness and the internalization of negative attitudes, race-based stress, and racial trauma that in turn will have deleterious effects on mental health.

Some communities have taken notice of this hate issue and decided to take a stand. To combat prejudice, xenophobia, and racism towards Asians, there are numerous Anti-Asian Hate movements in the US that have been operated during the pandemic. For example, after a wave of attacks against elderly Asian-American people in spring, the #StopAAPIHate movement was launched and obtained huge support from Asian-American public figures, politicians, and celebrities like Olivia Munn, Awkwafina, Daniel Dae Kim and John Cho, creating widespread coverage in US media (Hui, 2021). Along with that, in January 2021, US President Joe Biden signed an executive order with the Justice Department for a new guidance document on how to specifically report anti-Asian hate incidents (The White House, 2021).

Across the Atlantic, specifically in the UK, there are some movements and similar contributions to combat violence against the East and South East Asian (ESEA) community. Concepted in London, Besea.n, a grassroots movement set up by six ESEA women, aims to break negative stereotypes and change the lack of positive Asian representation in the media (Reid, 2021). Along with that, to directly combat Asian racism, there are some online movements such as Dear Asian Youth London, Racism Unmasked Edinburgh, and Asian Leadership Collective that offers online support networks to amplify voices and raise awareness about racism during this pandemic. In the next months, those online movements are planned unity marches organised by Asian Unity Over Fear UK and Pho Queue Crew—an Asian activist—to respond to the COVID-19 related hate crimes and violence (Hui, 2021). However, referring back to Reid’s writing, despite all its efforts, one must admit that the general support for ESEA’s anti-hate movements is nowhere near as high as it is in the US.

Along with that, there has been a global call for the health industry in this particular issue. Because health professionals play a key role in countering racism and its consequences, it is also important to ensure that the medicine field continues to care for all minority communities (Wu, Qian, & Wilkes, 2020). This is done so that there is no health gap between different societal groups, hence contributing to a healthier and more peaceful living and working environment.

In short, there is mounting evidence of offline discriminatory acts, racism, and xenophobia during COVID-19, whether offline or online. This triggered all political actors of various levels to disintegrate the hate, whether by using official policies or online movements. However, efforts to counter hate speeches that have been made, especially those via social media campaigns (e.g. the #RacismIsAVirus campaign started by a collective group of Asian-Americans) remains unclear (Ziems, He, Soni, & Kumar, 2020). One might even say that the amount of hate speeches continues to skyrocket, and countering efforts from the social campaigns has seem to take the opposing route.

This is such an ironic reality—there is a real pandemic haunting every single individual on the planet, yet humanity decided to create a new pandemic: racism. This hate act unconsciously created a big gap between Asians and the people around the world. Society has been plagued by a horrible idea, that this disaster is considered as Asians’ fault and Asians deserved judgement through a one way discourse. In the end, humanity might forget about COVID-19, the real enemy that we have to face and overcome.

Movements that aim on combating racism need to be appreciated and supported by every community, society, and personal body. It is essential for humanity to reflect upon this issue with a clear mind and try to face the situations without prejudice—especially towards minority groups. We are all facing the same pandemic, and life is already hard enough without any of us on each others’ throats. It is important for society and governments to salvage the impact of racism towards Asians. This can be done through making certain public policies that protect Asians (and other minority groups) and guarantee mental health support from official health institutes. At the end of the day, we owe it to ourselves to make this world a better place, lest it be the last thing we do as a healthy society.

Bibliography

Cheung, H., Feng, Z., & Deng, B. (2020, May 27). Coronavirus: What attacks on Asians reveal about American identity. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-52714804.

Croucher, S. M., Nguyen, T., & Rahmani, D. (2020). Prejudice Toward Asian Americans in the Covid-19 Pandemic: The Effects of Social Media Use in the United States. Frontiers in Communication, 5, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2020.00039

Gover, A. R., Harper, S. B., & Langton, L. (2020). Anti-Asian Hate Crime During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Exploring the Reproduction of Inequality. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 647–667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-020-09545-1

Hui, A. (2021, March 19). This Is What Anti-Asian Hate Looks Like in the UK. VICE. https://www.vice.com/en/article/4adzeb/anti-asian-hate-crimes-uk.

Reid, H. T. (2021, March 18). #StopAsianHate: Meet the people helping to tackle Anti-Asian racism in the UK. Gal-Dem Politics. https://gal-dem.com/anti-asian-racism-uk/.

Tessler, H., Choi, M., & Kao, G. (2020). The Anxiety of Being Asian American: Hate Crimes and Negative Biases During the COVID-19 Pandemic. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 636–646. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-020-09541-5

The United States Government. (2021, March 30). FACT SHEET: President Biden Announces Additional Actions to Respond to Anti-Asian Violence, Xenophobia and Bias. The White House.https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/03/30/fact-sheet-president-biden-announces-additional-actions-to-respond-to-anti-asian-violence-xenophobia-and-bias/.

Wu, C., Qian, Y., & Wilkes, R. (2020). Anti-Asian discrimination and the Asian-white mental health gap during COVID-19. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 44(5), 819–835. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2020.1851739

Ziems, C., He, B., Soni, S., & Kumar, S. (2020, May 25). Racism is a Virus: Anti-Asian Hate and Counterhate in Social Media during the COVID-19 Crisis. Cornell University Social and Information Network. https://arxiv.org/abs/2005.12423.

Cindy Amelia is a Law undergraduate student at Universitas Sriwijaya, Palembang, South Sumatera and one of ISAFIS’ Foreign Affairs Division Staff.