Kung Fu Hustle and Hong Kong’s Acceptance of Globalization

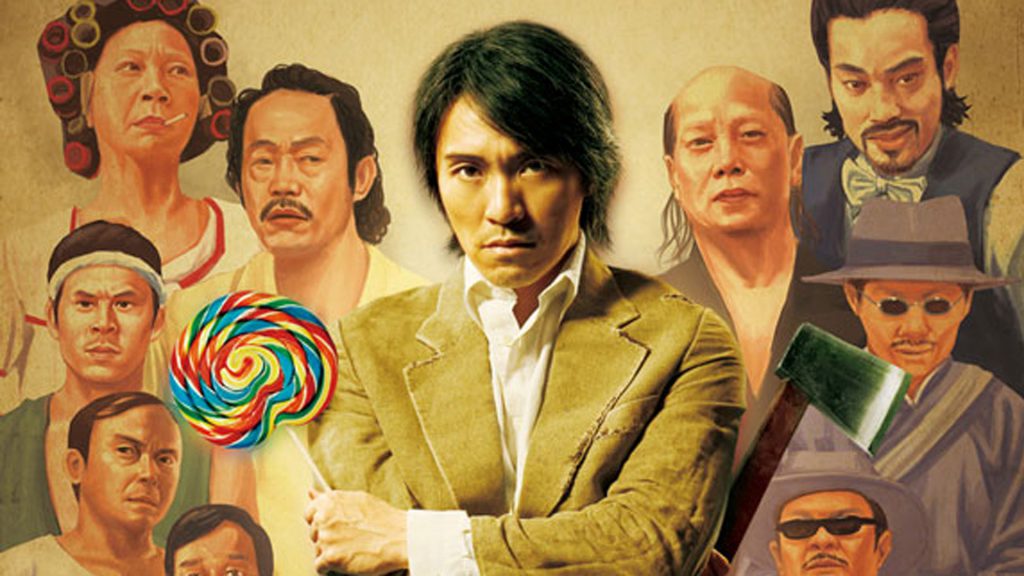

Illustration of the movie "Kung Fu Hustle". Photo: Cinema.id

Before the handover back to China, Hong Kong experienced a great economic period that saw them soar up to one of the biggest economies in Asia. By the 1980s, Hong Kong had become a successful financial bubble due to the blooming real estate market (Renaud et al., 1997). It is during this time that Hong Kong cinemas are able to take over the Taiwanese cinema as the biggest exporter of films in East Asia (Bordwell, 2003). In this booming period as well, names like Jackie Chan, Andy Lau, Leslie Chung, and the already departed Bruce Lee started gaining popularity through the exports of their films. This period can be considered a period where Hong Kong wants to be taken seriously by the world, marked with serious and melodramatic films flooding cinemas (Tan, 2016).

However, the bloom and happiness of the 1980s did not manage to last very long as the impending end of the British Empire approached. Hong Kong’s success in the real estate business has been attributed to their stability under the British reign that enabled the trust of foreign investors. That enabled them to create high budget movies with authentic Hong Kong storytelling, knowing that they did not have to pander to foreign audiences as their “exotic”-ness alone can draw foreign views. With the instability that surrounds the 1990s, the real estate business plummeted as investors and rich locals ran off as far from Hong Kong due to fears of unstable future economics. Their predictions would prove correct as the 1997 Hong Kong Handover coincides with the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis (Ho, 2011).

In the midst of change, an actor came bursting onto the scene to cheer the crying folks of Hong Kong. Stephen Chow has been producing the best comedies for the currently “sad” Hong Kong people. With his trademark Mo Lei Tau (nonsense) comedy being the most popular in Hong Kong with films like Fight Back To School series (1991-1993), Forbidden City Cop (1996), God of Cookery (1996), and King of Comedy (1999). The rising trend of nonsensical, slapstick comedy coincides with possibly the saddest period of Hong Kong. It mirrors how the mighty has fallen, with Hong Kong’s past reputation as a heroic and dramatic main character dashed to being merely a joke in the Asian cinemas. However, Hong Kong is desperate to keep their local products in its purest form. Even if everyone laughs at them, at least they are still 100% Hong Kong.

Hong Kong pretty much rejected the notion that they are nothing without their foreign investments. However, their stars said otherwise as Jacky Chan, Andy Lau, and Chow Yun Fat moved on to the US and mainland China to pursue their careers. As Shaolin Soccer (2001) by Stephen Chow managed to become a hit, but unable to capture enough foreign airtime as expected, Hong Kong reflected on their notion. Stephen Chow himself has stated that the local market is too small for Hong Kong cinema to grow (Gilchrist, 2012). But that did not stop him from hiring only his friends and locals as actors for the Shaolin Soccer movie. Eventually, the movie succeeded in becoming a hit, however outdated special effects became the main comedic focus instead of the actual jokes in the movie. Chow sensed that “original” Hong Kong cinemas are impossible to stand alone without jokes pandering to the global audiences and decided to try again in his next creation.

Kung Fu Hustle (2004) is a film that I consider as the sign of Hong Kong’s acceptance of globalization. Seven years after the handover and inability to return back to their glorious financial days made Hong Kong desperate for a return to the international stage. In Kung Fu Hustle, Chow remedied his mistakes in making exclusive jokes and started to pander to the international viewers. He also included more references to western culture by taking advantage of outdated effects to reference old cartoons like Road Runner and hiring Yuen Woo Ping who have worked on The Matrix (1999) to choreograph the fight scenes to bring more modern western appeal. Chow also enlisted the help of Sony Pictures to help distribute the media from the start to make sure it hits the foreign market greatly (Szeto, 2002).

In this movie, Chow symbolized the death of traditional Chinese Wuxia films by portraying Kung Fu masters as lowly workers living in the Pig Sty Alley. The film portrays a mafia group that managed to overpower Kung Fu masters with the use of weaponries. Although the main character portrayed by Chow surpassed the mafia at the end, he did it with the “Buddha’s Palm” technique which is not a traditional Kung Fu style and more of a CGI based fantastical attack. The main character also becomes a normal candy shop owner at the end of the movie, meaning that none of the “Kung Fu Masters” of this film managed to reach heroic highs such as portrayed by Jackie Chan or Jet Li’s films.

The western cultural references provided by Chow in this film is perhaps shown by his numerous dialogue references to western works. One of the characters, Donut, quoted “with great power comes great responsibility.” which is a famous quote from Spiderman. The mafia boss is characterized to be more like Robert De Niro’s character from The Godfather (1972). Not only that, Chow brings more Chinese elements that are accustomed to western viewers like the white outfit he wore in the final battle which is a similar outfit to Bruce Lee’s outfit in Enter The Dragon (1973) and a stereotypical soundtrack of traditional Chinese music. He also abstained from using traditional Wuxia fighting style choreography and shifted to Western choreography by hiring Yuen Woo Ping. This time he hired more famous actors and even convinced “Bruce” Leung Siu Lung to come out of retirement to play the main villain of the movie. Since Leung was a prominent Bruce Lee impersonator, this gives an iconic meaning to his defeat. It feels like Chow is killing Hong Kong’s rejection of their fall and death of “pure” Hong Kong cinema by defeating a phony of its greatest actor.

Chow symbolized to Hong Kong through this film that they need to move on from their traditionalist belief and accept globalization as it is. Hong Kong is no longer the heroic Kung Fu fighter that everyone strives to be, instead they’re just a part of an international system. However, this realization does not mean that Hong Kong should be a villain to “become strong” again like what the main character does in the movie. Instead, Hong Kong needs to accept that time is changing and they should welcome all possibilities of the impending globalization. Kung Fu fighting just isn’t worth it anymore, and they eventually have to find regular jobs.

The success of this film revolutionized Hong Kong cinema to a more global stage as they started to abandon more traditional films and started adopting western tropes. This also started the integration of Chinese and Hong Kong cinema as more Hong Kong based creators took their talents to the mainland to create a larger market for themselves. Stephen Chow set a tone that Kung Fu is not something that is exclusive for “unbeatable heroes” by integrating his Kung Fu to a comedica main character. This will later spawn the Kung Fu Panda series which has a pathetic hero who learns Kung Fu to strengthen himself. His choreography also revolutionized Chinese films with the IP Man films taking notes from Kung Fu Hustle’s fighting choreography, albeit with less humor.

This film is a striking reminder of the effects of globalization towards the identity of a culture. Chow managed to craft something that feels exclusive to Hong Kong cinema, but at the same time made it enjoyable in the West. While some films like IP Man and The Wandering Earth have successfully used Chow’s formula, some have totally bastardized it. Thousands of Chinese knockoff films or films that abuse western tropes have also plagued the Chinese market. For example, the film “Pure Hearts: Into Chinese Showbiz” was slandered after trying to accommodate 11 western plotlines in one movie to garner western audiences.

Whether globalization is a bad thing or not, Chow has shown that changes need to be accepted and adapted by. His capability to combine traditional Wuxia style films with western comedy is proof that changes need to be made to make a media a global media. What Chow did is no less different than what fusion restaurants do when they add western toppings like sausages on sushi. Hong Kong, more or less, has been bursted from their small bubble market and is now facing a real world market. Being stubborn and rejecting globalization won’t bring any benefit other than a needless pride. Hong Kong accepted their fall and managed to save themselves from a complete economic breakdown by accepting the needs of foreign pandering in the age of globalization just like what Stephen Chow did.

References

Bordwell, D. (2003). Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and The Art of Entertainment. Harvard Univ. Press.

Gilchrist, T. (2012, May 19). Interview: Stephen Chow. IGN. https://www.ign.com/articles/2005/04/21/interview-stephen-chow.

Ho, S. (2011, December 19). History Lesson: Asian Financial Crisis. Spy On Stocks. https://web.archive.org/web/20151117133309/http://spyonstocks.com/history-lesson-asian-financial-crisis/.

Renaud, B., Pretorius, F., & Pasadilla, B. (1997). Markets at Work: Dynamics of The Residential Real Estate Market in Hong Kong. Hong Kong University Press, HKU.

Szeto, K.-Y. (2002, October 20). The Politics of Historiography in Stephen Chow’s “Kung Fu Hustle” . JUMP Cut A Review of Contemporary Media. https://web.archive.org/web/20070925122214/http://www.ejumpcut.org/currentissue/Szeto/index.html.

Tan, S. K. (2016). Tsui Hark’s Peking Opera Blues. HKU Press.

Albert Julio is an International Relations student at Universitas Indonesia. He can be found on Instagram with the username @im.the.aj