The Art of Resistance in Thailand

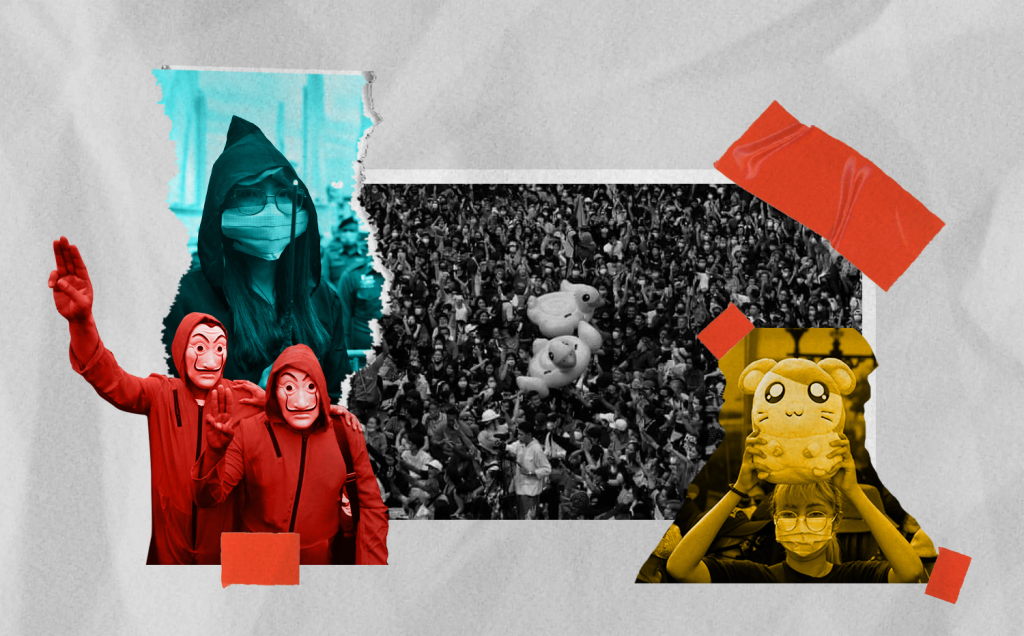

Powerful resistance from the Thai youth. Illustration: Kontekstual

Following the discourse of inclusiveness, strategies, and the ways in which demonstrations in Thailand throughout 2020 are carried out has lured the discussion to find the clarity as well as to conceptualize what constitutes the ingredient of non-violent resistance in Thailand. World history has shown that the revolution–whether left or right agenda–requires a certain organized movement, which challenges the establishment and puts pressure toward the status quo. Unfortunately, such a revolutionary movement is often undertaken in a coercive manner. However, as countries around the world have adopted the democratic system in the sense of its procedure, resistance points of domestic actors have been better accommodated through various ways. The ways in how civil society organized the movements oftentimes reflect how serious these issues are. A combination of democratization, populist politics, and direct-rule-by-the-people has colored the political dynamics in which a high degree of resistance is equal to a high degree of violence, hence justifying violent movements. However, that is not the case in Thailand, where the movements have pursued non-violent resistance.

Indeed, a political comparative analysis is a complex issue. It can’t generalize one single determinant, which is framed as the main variable, to be the most influential factor in identifying the response of the society or the government in regard to the democratization movement. One country’s political culture, institutions, regimes, and actors might differ from other countries. On the other hand, other factors such as socio-economic catastrophe, coupled with the decrease of the aggregate demand, and eventually, economic recession might also drive the movements to challenge, if not demand, the government to provide better fiscal policies – or in an extreme measure, to ask the government to step down. In this regard, there have been significant numbers of research in identifying the root cause of such resistances – ranging from different perspectives, disciplines, and levels of analysis either international or domestic pressures.

As stated above, Thailand is one great example of how such resistance movements persist. It was started when the Future Forward Party (FFP) – an opposition political party whose members are mainly youths – has been dissolved by the constitutional court in early 2020. As a newly born party, the FFP had secured 80 seats in the parliament in the 2019 election. Following the result of the dismissal of FFP in which Prayut – ex-military coup leader who is now the prime minister – had wielded power over the court, student-led movements in turn organized demonstrations to oppose the verdict, arguing that the banning of FFP was a systemic effort to lessen the oppositional power. In a healthy democracy, the opposition is a necessary force to balance the power. The case of Thailand, whose political system is a constitutional monarchy and ‘procedural’ democracy, exemplifies that there is a contradiction of ‘democracy’ – a concept that has been taken for granted. Instead, what we have found in Thailand is an autocracy, despite the contending interest between the legitimate government, monarchy, parliament, and military.

Indeed, the term of success in resistance has been widely contested. There is no exact measurement of the success of such movements. It is either failure or success. While physical coercion is likely to be implemented by the regime intended to restrain the movements, it would instead result in the increase of internal solidarity of the resistance movement, as one lecturer in political science, Thammasat University has put forward. However, this paradox has been the case elsewhere too. Further, civil resistance is disruptive in nature. Its goal is to object to the opponents, in this case, the status quo. Therefore, things that differentiate between one resistance movement to another would be the strategies, which require strategic analysis in order to organize a ‘successful’ movement – where intellectual figures come in.

On the other hand, civil disobedience has been arguably embedded in Thai youths. One factor that explains why they are doing so is that globalization accompanied by the increasing flow of information and knowledge has shaped the way Thai youths live. They started to confront the culture and resist the norms. This expression is manifested through the use of arts, song, gender, identity, etc. It actively demonstrates how the class struggle among Thai youths manifested their nonconformity to what the monarchy and the regime have dictated for years.

Within the year 2020, many demonstrations have taken place, starting in the early of February in Thammasat University. The peaceful protest started with reading poem, articulating demand, and voicing out their concerns. However, that was not effective. This student-led democratic movement started to think differently in order to grasp wider attention and sympathy from the public. They sang the Hamtaro song. They organized K-pop dances. LGBTQ+ movements also organized several protests. They wore Harry Potter costumes. They marched to the democracy monument and other places. There was also a time when Free Youth and United Front of Thammasat and Demonstration had successfully organized a bait for the police in which they posted an announcement that there would be a big surprise – and turned out, the big surprise was there is no surprise. These organizers also asked students to wait at the nearest BTS station and would announce the place of the demonstration through Telegram 15 minutes in advance because otherwise the police would have known where the demonstration would take place.

Although horizontal conflict is unavoidable, the democratic movements in Thailand seemed to be united as they have repeatedly opposed the government, or Prayuth in particular, as their referent object of the common enemy. Instead, the conflict at the bottom is apparent between the conservative ‘yellow’ ultra-royalist and democratic student-led movements. There were also monks and a few police who sided with the democratic movements. It demonstrates that these repeated, collective, consistent, small-and-big, inclusive, and non-violent movements have attracted public sympathies instead of marginalizing those who are apolitical to begin with. Even though they did not claim themselves as non-violent movements, they have learned to face and bear the state’s forces if necessary. It is where the milk tea alliance has provided extensive supports, including knowledge, strategy, and other assistance. In particular, Thai protesters have learned from what has happened in Hong Kong. While there have been great forces at the bottom in contesting the legitimate governments through different forms of demonstrations and rallies, the vertical relations between the state and civilians appeared to be the hindering structural factor as to why many movements so far have not been successful in bringing their agenda.

Such an art of resistance has no one size fits all approach. Some of them, particularly the inclusiveness within the civil society in organizing non-violent resistance, perhaps is the most valuable tool to increase public awareness, sympathy, and support. It shows that the agenda of democratization belongs to everyone.

Muhammad Maulana Iberahim received his MA in Asia-Pacific Studies from Thammasat University (Thailand). Reach him through @iberahims